This essay was written part way through Spore’s development, and summarizes one of the biggest transitions the project made — unknown to many — from what could have been a SimEarth like game/science toy to a capital-G computer Game. It tells how Spore made some of its early, and most crucial, navigational decisions down the branches of design possibility, to use Will’s own language. I feel like a discussion of how Spore turned out versus audience and developer expectations is a whole other story that should be distilled and told, but this is not the place for that.

Originally published in Third Person, edited by Pat Harrigan and Noah Wardrip-Fruin.

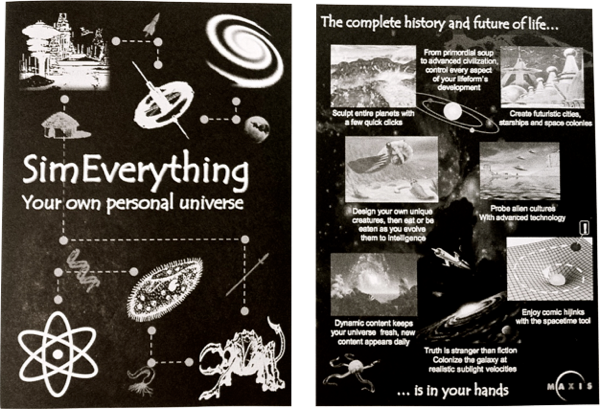

Spore grew from Will Wright’s fascination with the vastness of the universe, and the probability that it contains life. Wright linked Drake’s equation, which computes the probability of life occurring in the universe, with the long zoom of Eames’ Powers of Ten film. Each term in Drake’s equation corresponds to a different scale of the universe, and a different zoom of the Eames’ film. “Spore†stood for the spread of life through the universe: minute seeds of life hopping from one planet to another, either as bacteria riding comets, as panspermia theorizes, or intelligent beings on spaceships.

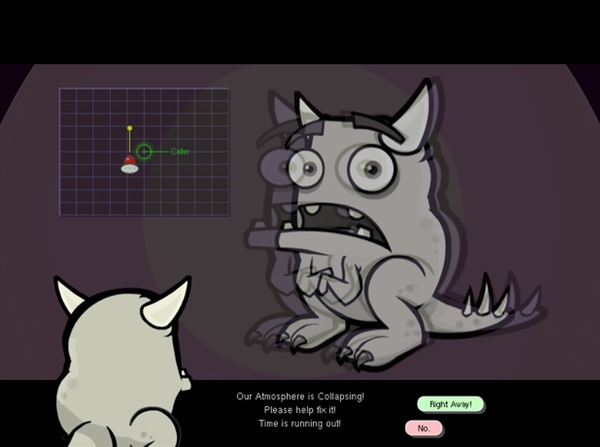

Early Spore prototypes and design concepts focused on simulating the movement and evolution of alien creatures, fluids, the birth of stars, galaxies, nebulae, and the spread of intelligent and non-intelligent life in media as small as a bread crumb, and as large as a galaxy. There was a galactic potter’s wheel, where you could try your hand at forming a stable spiral armed galaxy. A blind watchmaker interface allowed you to guide the evolution of novel life forms. You could sculpt huge piles of gas into stars that were just right for life. Will’s idea, at this point, was that players were to directly experience the difficulty and frustration of making life in the universe, and appreciate the improbability that life exists at all.

I initially joined the project at this early prototyping phase, when Spore was no more than a handful of people, and felt less like a game development project, and more of an awesome research and simulation endeavor. To me, the project was an intellectual love letter to all of existence, a depiction of the entire universe as a complex of interlocking self-similar systems. Patterns emerged ― everything, from disease to culture and space travel could be represented through some combination of cellular automata, agents, and networks. This was my summer dream job: make toys about anything in the universe, using everything I knew about interactive graphics and simulation, for the greatest simulation connoisseur in the world.